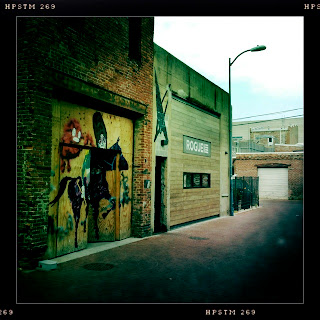

I entered Blagden Alley looking for food. What I found, instead, was revolution.

Before revolutions come confessions, however. And this:

I am not supposed to write about Rogue 24. The purpose of this blog is to

celebrate the efforts of journeymen cooks and streetfood purveyors who serve

truly delicious, often remarkable food easily within the financial reach of men

and women of the American proletariat working class. Haute cuisine establishments peddling so-called “molecular

gastronomy” to affluent eaters with far, far more sophisticated palates than my

own have strictly been off limits since I started this little binary enterprise

in food writing a year ago, however often I might work with their chefs, or

patronize them myself as eater and enthusiast extraordinaire. The chance encounter with culinary

excellence at a roadside diner whose smoking grill cook is ashing his Pall Mall

into the homefries holds far more excitement and, in my opinion, is vastly more

deserving of celebration than, say, the gastronomy of a three Michelin star

establishment whose excellence is expected and is, after all, a matter of

course.

So why Rogue 24?

Why now? After all the ink

that’s been spilt on the restaurant and its Chef/Operator RJ Cooper, why lift

my own pen and add to the fray?

Because I think RJ’s detractors have gotten him all wrong. I think there has been a fundamental

misreading of Cooper’s personality, his culinary aesthetic, and what Rogue 24

sets out to achieve every time Cooper and his team suit up in their whites. RJ could have dumbed it down. He could have opened a pizzeria. He could have opened a barbeque

joint. With the street cred

surrounding his James Beard Award and all the celebrity chef buzz following his

remarkable appearance on Food Network’s Iron

Chef, RJ could have opened a cupcake stand and made a killing. But he didn’t. Instead, he built one of the finest, most

challenging restaurants in Washington and in one of the most unlikely

places. Cooper clearly endeavored

to reinvent the restaurant experience for Washington eaters, transforming it

into a journey, a thrill ride, while all the time, and with his usual brash, two-fisted

swagger, attempting to create a cuisine that Washingtonians had never before

seen. He tried, as is still

trying, to reinvent the wheel. My

meal at Rogue 24 last year was easily the greatest single meal of my life. Do I say that of Cooper and Rogue 24

simply because I’m just a culinary simpleton from Missouri farm stock too

easily impressed by the dazzle and flash of big-city gastronomy and the cult of

chef celebrity? Maybe. Or do I now sing Rogue’s praises

because I’m a food careerist with over twelve years in the business and maybe,

just maybe, I know what I fuck I’m talking about? Maybe, just maybe, I’ve put in the hard time to know when chef

like Cooper is putting his soul into his work and leading with his heart. What I experienced at Rogue 24 was,

truly, nothing short of transcendent.

More than just a meal; it was an experience, and its why we pay chefs

like RJ Cooper to cook for us, because when they cook as well as RJ does, the

journey can be transformative, and we leave a restaurant like Rogue totally

stuffed, more than a little drunk, and forever changed. Because RJ shows his patrons what new

possibilities in American gastronomy lie in wait, and how thrilling a

restaurant experience can be if the patrons are willing to let go, chill out,

and enjoy the trip.

Another confession.

Chef RJ Cooper.

I know the man. I have worked

with him several times over the last few years at fine events in and around the

Washington area. This, however, is

not to suggest we were destined to be pals. If anything, it’s quite the opposite. It means we were initially disposed to

hating each other’s guts in the deep and abiding way dogs hate cats. He was the celebrity chef with the

Beard Award, the awesome motorcycle and the great hair. I was the front-of-house guy only very briefly

famous for a spread done on me in the Washington Post, and whose waiters were going to find a way to fuck RJ’s shit

up. RJ and I have had several

successes together, and maybe, just maybe, RJ has, over the years, found

something to like in me. Our

luncheon for a Spanish/Japanese interest with world-famous chef and three

Michelin star, Basque mac daddy, Juan Marie Arzac, (which I most certainly did not fuck up) comes to mind. But while I have found much to admire in

Cooper, liking the guy does not make me his apologist. I’m not shilling for RJ here to generate

covers for his restaurant, and I’m most certainly not his bitch. RJ can take care of himself. He’s good-looking enough to break

hearts, and big enough to break jaws.

But I believe that beneath all those tattoos and Harley Davidson smoke

and caustic, in-your-face swagger, beats the heart of a poet, a truly nice guy

who just wants to cook for a living and, while at it, change the face of

American gastronomy one perfect bite at a time.

The first element of Rogue’s genius lies in the idea of

removing choice from the restaurant experience. Instead of being handed a leather-bound menu thick as the

Los Angeles phone book, and later in the meal, an equally daunting wine list by

a smirking sommelier, you are, at Rogue, asked to make two choices and two

choices only. They are these: how many courses do you want to eat (a

16-course progression, or the 24-course full monty), and are you drinking

alcohol? That’s it. That’s all you’re asked to decide. And with those decisions made, you are

then invited to relax, sit back and enjoy the magical carpet ride that will,

for the next three hours, take you into a culinary wonderland of startling

textures and flavor pairings so daring that before you know it, dinner at Rogue

has become a rush. It’s as if

adrenaline is the magical, secret ingredient of RJ’s cooking, and it builds,

incrementally, throughout the night, until dinner at Rogue is suddenly more fun

than that time you stole your father’s red convertible to satisfy the pure and

simple wonder of discovering how fast you could go. Eating at Rogue is exactly like that. You don’t exactly know where you’re

going, and you don’t know what’s around the next corner, but you can’t wait to

find out what lies ahead.

Even more central to Rogue’s genius, perhaps, is the idea

for design of the restaurant itself:

heighten the Rogue experience by putting an open kitchen in the middle

of the dining room and having RJ and his team of cooks serve the tables

themselves. Waiters fuck off, who

needs them. If what Food Network

peddles is correlative to food porn, then what Rogue is selling is the chance

for patrons to lube up, put on a jimmy, and join in on the fun. It’s also the area where RJ shines more

brightly than any chef I’ve ever worked with, for without the Food Network

lights and cameras and makeup, there around the kitchen of Rogue, you see how

fucking hard it is to be a chef.

You get a real and palpable sense of how demanding it is to forever be

on your feet, in the unrelenting heat of a working kitchen, and how taxing it is

to concentrate that long, that hard, on each and every plate that leaves your

line, night after night after night, year after year. Putting a chef, any chef (especially a raging perfectionist

like RJ), in the middle of a dining room is an act of daring, a recipe for sure-fire

disaster akin to burning down a fat one while pumping gas; bad things are sure

to happen. Except at Rogue. Twice in my meal at Rogue, RJ spotted

two things that raised his famous ire.

The first was that my napkin had fallen to the floor and none among his

staff had provided me with a new one.

Second was the fact that my plate, for one of the courses, had not

received enough fois gras (his estimation, not mine), so over came RJ himself to

remedy his sous chef’s error. I

realize these service gaffs may seem like piddly shit to you, inconsequential,

undeserving of a chef’s attention.

But to me it meant the world.

This is what I fucking do for a living. I shape the experience of clients by paying attention to the

shit you wouldn’t think matters. You

can’t fake paying attention like this.

So to have a chef of Cooper’s stature noticing napkins on floors and insufficient

fois gras amounts on plates tells me (as it should you) that this guy Cooper

isn’t phoning it in. It tells me

RJ is the real deal. It tells me

that cooking, for RJ, is much like a street fight, that the dude is always

ready to rumble, and that ten-to-one suckers, I betting RJ’s going to drop his

man.

The third and final component in Rogue’s mad trinity of

culinary genius is, of course, the food itself. But I’m not going to write about RJ’s food because I’m not

qualified. I haven’t spent the

last twenty years trying to redefine American cuisine by taking it apart and

putting it back together again the way you dismantle and reassemble a favorite

uncle’s Dodge Charger (only to find that it now runs faster). For critiques

of RJ’s cooking, I send you to Yelp, where every douchebag out there working in

a cubicle, wearing khakis, and carrying a wallet deigns himself qualified to

publically criticize the life’s work of truly great chef’s just because he

doesn’t understand what he’s eating or what the restaurant is all about. Suffice it to say that when RJ appears

tableside with instructions on how best to consume the next course (“inhale the

smoke first” or “chug it like a beer”), you realize that you’re not in Kansas

anymore, Dorothy, and that the dish before you in no way resembles anything

served at grandma’s house, and that culinary revelation is waiting for you at

the end of your fork.

I’ve followed the press on Rogue for a year now the way a baseball

fan follows news of a favorite team.

In none of the coverage, however, have I ever sensed that any critic

“gets” Rogue 24. Why, for

instance, has no critic explored RJ’s motives in locating his restaurant in an alley, for fuck’s sake, in one of the

most violent (until recently) neighborhoods in DC? Why has no critic considered RJ’s place of birth (Detroit)

and how that might inform the way he approaches gastronomy? Why has no critic “read” RJ’s own personal

aesthetic and decoded the lack of bullshit in his tattoos, his Harley, his

taste in music? That ain’t trendy,

people; that’s real.

My theory, posited for your approval, in the form of an

equation:

RJ Cooper + Rogue 24 = the culinary equivalent of punk

rock. And not just any punk

rock. I’m talking Iggy and the

Stooges rolling naked in broken glass and peanut butter, Detroit style.

RJ and I are from the same place. Not the same city, mind you (he’s from Detroit; I’m from

D.C. via Missouri), but the same mindset.

We are both from happy, white, middle class families. We were both, as children, fed and

loved. But somehow we both decided

to say fuck it to our families for

the far more dubious pleasure of inhabiting the punk/post-punk club scenes of

our native cities. And while I was

being kicked in the face by the bare-footed Henry Rollins at the original 9:30

Club on F Street, RJ was being stabbed (three times!) in the chest at a 7

Seconds show in Detroit. And just

how tough was Detroit back in the day (as if it’s not now)? When I first visited Detroit (think early-90s),

I was touring with an awesome rockabilly band, Three Blue Teardrops. I was filling in for my friend Rick on

bass. The minute I first stepped

onto a Detroit sidewalk, a man walked up to me and said this: I’m

going to kill you. Three songs

into our first set, someone threw a beer bottle at me, shattering it across my

bass. Tough city. Such is RJ’s pedigree.

When I look at Rogue, I see perhaps the only haute cuisine restaurant

in America that truly and purely embodies the punk rock ethos unique to our

generation. When I look at the

place in Blagden Alley, I see a restaurant that says, fuck off, you’re not cool enough to eat here. But when I consider RJ’s cooking, I see

a culinary effort that strives for purity, and that is trying to change the

world. And that’s punk rock in a

nutshell, folks. It’s about brutal

honesty. It’s about trying to

change the world by tearing it down and searching for the essential truth

therein. Why no food critic has

yet drawn the comparison between Rogue 24 and punk rock is beyond me.

And just to get it off my chest, I’ll conclude with

this: “molecular gastronomy”

happens every time you poach an egg, so let’s move on and look more deeply at

what RJ (among others) is really doing with food.

And yes, Rogue 24, is expensive, to be sure. But you should eat there. At least once in your lifetime. Because RJ is easily one of the best

cooks of our generation. And if

you care anything about the course of American gastronomy, you’ll want to have

something to tell the kids.